SPORTS FOR A BETTER NEIGHBOURHOOD

Every evening, two sisters from Bamako gather the children from their neighbourhood on a sports field. Through sport, they teach them lessons about life, and the neighbourhood becomes closer. 'Now everyone comes to get me if I'm not on the field at seven o'clock.'

Bamako has grown rapidly. From a town no bigger than Venlo (100,000 inhabitants) when Mali gained independence in 1960 to half a million twenty years later. Over the last thirty years, entire neighbourhoods have sprung up, with little infrastructure, hardly any electricity or water, and people who don't know each other.

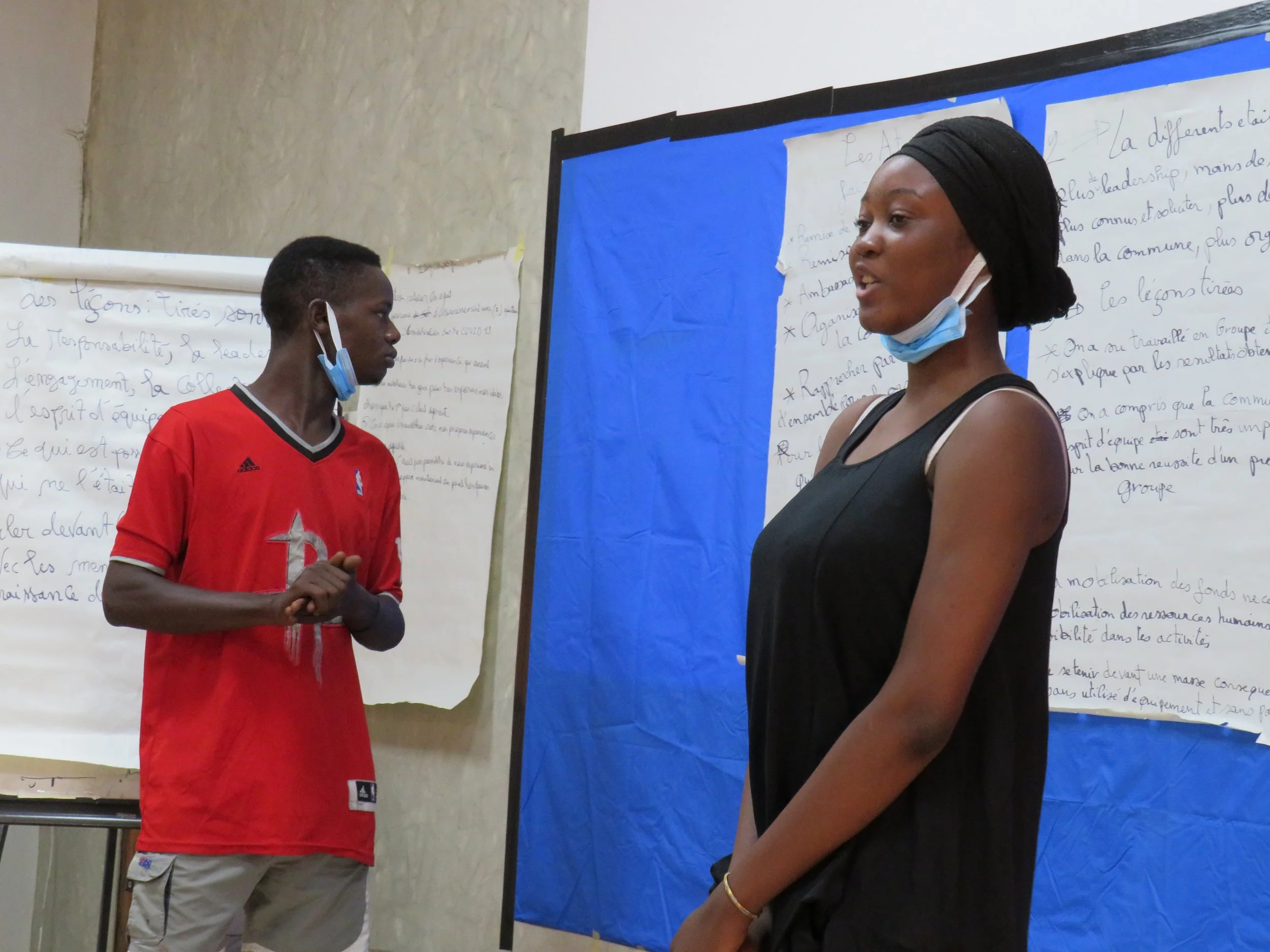

Fatoumata (21) and Aminata (19) Coulibaly want to do something about this. They both want to bring some structure to Doumanzana, their neighbourhood, through sporting activities. Coherence is the magic word, although they themselves prefer to use the term solidarity. They know by now that this is a lot of work. The neighbourhood has been the scene of riots and robberies, even in the recent past.

It runs in the family

They have known sport since childhood: they grew up in a very sporty family. 'My father trained the national football team,' says Fatoumata. Sport still plays a role in their lives, albeit a modest one due to their busy study programme.

Every evening at seven o'clock, they can be found at the local sports ground. The young people run en masse, play football and play games. How did this come about? Fatoumata's answer is short and makes us smile. Fatoumata's answer is short and elicits a burst of laughter: 'So it's all because of my sister.'

But then Aminata's expression becomes serious as she explains her motivation. 'I noticed that young people in my neighbourhood no longer respected their elders. That's important to us; it's part of our tradition. I set up sports activities because they're a way of getting messages across, especially to the youngest children.

'They find the activities I organise interesting, and afterwards I start conversations with them. We started with a small group in March this year: five children. Now the whole neighbourhood comes to get me if I'm not on the field at seven o'clock.'

It didn't happen automatically, says Fatoumata: 'In the beginning, it wasn't easy to convince parents to let their children stay outside for two hours. Parents thought their children would use sporting activities as a cover to do completely different things that they weren't allowed to do at home. That frustrated us quite a bit in the beginning.'

Did they talk to those parents? Aminata: 'No, not really. We showed them, through the things we organised and the results we achieved.'

Fatoumata adds: “The advantage is that the children get exercise, which means they have less time for things that are bad for their health. And when they've finished exercising, all they want to do is sleep. So that's very good...”

Side effects

The sisters subtly combine all kinds of life lessons, such as teaching respect, with their sporting activities – and it's catching on. The idea of bringing respect back to the neighbourhood is working as a way to achieve greater social cohesion. To the great delight of the elderly, the young people have started greeting them again. They emphasise that this is important: it is the ultimate expression of respect.

And so local residents start talking to each other on the street. Aminata sees that the neighbourhood has become more sociable.

Have they themselves gained more respect through their work? Fatoumata is certain of it. 'Definitely. That's mainly because we show dedication, which is appreciated. But I've also seen that you can achieve more through our sports activities because you hold the attention of young people. It works better than just talking to them. You can have fun with sports and games and at the same time pass on information, which then sticks better.'